Synagogue built in: 1825-1826

Earliest record of community: 1810

Last rabbi:Dr. Israel Taglicht

Pogrom Night: Minimally Damaged

After 1945:Community synagogue

Today: Community synagogue

Summary: The history of the Stadttempel (City Temple) began at the end of the 18th century in the Sterngasse. At this time a few officially tolerated Jews gathered for worship in the damp cellar of the house ‘Zum Weissen Stern’. In 1810 the Dempfingerhof [now Seitenstettengasse 4] was acquired and on September 4th 1812 the Synagogue was consecrated. Moses Fischer served as Rabbi and then as Dayan (rabbinical judge) till 1829. Soon the premises became insufficient and the Dempfingerhof was demolished and in 1825 the foundations were laid of a new Synagogue designed by the Architect Josef Kornhaesi.

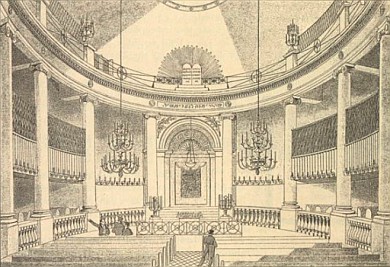

On April 9th 1826 the Synagogue, with seating for 1,500 persons, was consecrated in the presence of distinguished city officials. It was described as being designed in the spirit of the “Toleranzpatent” in that its distinctive features were not visible from the street, but the domed interior and the triumphal arched western entrance were very striking as was the light-filled structure contrasted with its sombre surroundings.

Isaak Noah Mannheimer from Denmark was engaged as the first preacher of the congregation and his wisdom and sensitivity ensured the future unity of the Kultusgemeinde throughout a period of division and tension. He developed the so-called Mannheim Order of Service giving certain concessions to the need for modernisation without sacrificing the traditional soul. Salomon Sulzer from Hohenems was chosen during the first year of the synagogue’s existence as the main cantor of the congregation. His new style of synagogue music not only became standard in Vienna, but permeated Hazzanut (translation?) throughout the Jewish world.

In 1828 the communal leadership invited Rav Eleazar Horowitz from Floss in Bavaria to act as Dayan. The strictly orthodox disciple of Moses Sofer (“Chatam Sofer”) was the accepted rabbinical authority of the Kultusgemeinde till his death in 1868. Mannheimer cooperated with him in a spirit of mutual understanding, and the Polish Jewish community in Vienna regarded him as their spiritual authority.

Mannheimer’s successor was Adolf Jellinek, formerly Rabbi in Leipzig, who was engaged in 1856 by the Leopolstadt Temple in Vienna and in 1856 moved to the Seitenstettengasse where his gifted and renowned style of preaching evinced universal admiration.

On Rav Horowitz’s death in 1868, he was succeeded by Rabbi Moritz Moses Guedemann, conservatively inclined, originally from Hildesheim nr. Hannover, who had been engaged the previous year as Communal Rabbi of the Leopoldstadt Temple. At first engaged as Av Beth Din (President of the Court) his speaking ability and wide cultural knowledge qualified him also for the position of preacher for the Stadttempel and following Jellinek’s death in 1893 he inherited that position also. A follower of the Samson Raphael Hirsch school, strictly observant and with a high level of secular knowledge, he was an ideal successor of Jellinek, able to safeguard the unity of the congregation which was subjected at that time to succeeding waves of reform movements. He broke the mold of the typical temple rabbi, beardless and with flowing locks – he was proud to be identified as an orthodox Jew, all his portraits show him full bearded with the traditional rabbinical skullcap. At the request of ultra orthodox circles, Salomon Spitzer, Rav of the “Schiffschul” was co-opted on to the Beth Din (Law Court).

The year 1892 saw the introduction of the post of Chief Rabbi [Oberrabbiner]. The new constitution set at the head of the community an elected executive committee. The Chief Rabbi was responsible for the preaching of sermons and all communal activities. Weddings were celebrated by the Rabbis of all Synagogues and associations affiliated to the Kultusgemeinde. The Beth Din attached to the community, officially designated as ‘’The Rabbinical College’’, was responsible for all matters connected with Jewish law and tradition, divorces, settlement of disputes etc. To accommodate the requirements of the ultra orthodox, an Av Beth Din, described in the constitution as ‘’Rabbinical Asessor’’, who was accepted by the ultra orthodox was to be appointed. By this means the unity of the community was to be preserved.

In 1899 Rav Meir Meirson, born in Brzezany, Galicia, arrived in Vienna as Rav of the Polish Shool in the Leopoldsgasse. The general community appointed him as Av Beth Din with the responsibility of providing religious services to satisfy the requirements of the strictly observant. He was later appointed Hon. President of the ‘’Machsike Hadath’’ which served as the spiritual centre of the ultra-orthodox.

Dr. Zwi Perez Chajes was called to the position of Chief Rabbi of Vienna in 1918. His main achievements lay in education. On his initiative two comprehensive schools and the Castellezgasse grammar school were founded, which later was named after him on his early death in 1927 at the age of 52. . [His school was re-opened in 1984.] His successor was Dr. David Feuchtwang, who since 1903 had been Rabbi in the 18th district Schopengasse Synagogue.

In 1933 Rav Josef Babad succeeded Rav Meierson and upheld the faith of the congregation in very difficult times. He remained in Vienna till 1941 when he made his escape to Holland, and eventually to England. In 1932 the well known Mathias Matitjahu Matjas was engaged as first cantor in the City Temple and Marcus Mordechai Balaban as second cantor, both were later murdered in concentration camps.

Following Rabbi Feuchtwang’s death in 1936 Dr. Israel Taglicht was appointed as Chief Rabbi. A native of the Ukraine, he had been in Vienna since 1893 as Rabbi of the Turnergasse Synagogue, he remained in the position of Chief Rabbi till 1938. In the course of the outrages Viennese Jewry had to suffer following the take-over of Austria by Nazi Germany in March 1938, even the 76 year-old Rabbi Dr. Israel Taglicht was forced to his knees to scrub the streets. His dignified behaviour caused even the bystanders to realise that this faithful believer did not deserve such treatment and he was allowed to depart to his home. He was eventually able to leave for England and died in Cambridge in 1943.

One often reads that the City Temple was not destroyed during the November Pogrom so as not to endanger the neighbouring buildings. In actual fact, the reason that the Seitenstettengasse did not go up in flames was the firm instructions of SS Police Chief Mueller in Berlin to safeguard the communal archives in the building next door containing the register of the whole Jewish community, thereby to facilitate their subsequent arrest.

Although the building was not destroyed, the interior was completely ruined.

During the war the city temple was in fact the only synagogue in Vienna where services were held. Under wretched conditions a few remaining Jews would gather together for worship. Until the very end of the Nazi regime services were held there. Rabbi Benjamin Murmelstein, who before the war ministered to the Kluckygasse synagogue in the 20th district, functioned as Rabbi and was designated by the Nazis as head of the Jewish community [“Judenaeltester”] He had to steer a very narrow course between aiding his co-religionists and appearing to co-operate with the authorities, a situation often arising in the history of other “Judenraete” in the Nazi period.

To consider the “Kultusgemeinde” as an organisation one must take into account the flexibility with which at breakneck speed changes and adaptations were made in a feeling of brotherly sympathy to accommodate the requirements, within the community of a rapidly growing and increasingly divergent membership. Beginning with the desire of a small group of officially tolerated Jews for a fixed place of worship, a whole organisation developed under the leadership of distinguished professionals and businessmen which since 1890 had provided for all Jewish communal requirements in Vienna.

The tendencies towards disunity evinced between the masses of ultra orthodox Hungarian “Oberlanders” for example and the distaste of some of the Viennese for some of their requirements, such as the communal upkeep of the mikvah (ritual bath), showed that the community was ready and willing to accommodate all its members. The Kultusgemeinde set about integrating the vast stream of refugees from Galicia into communal life in spite of the fact that the typical “Ostjude” hardly fitted the Viennese image, and the community developed an extensive programme to improve the economic standing of the Galician community. Having developed into a vast complex organisation, the Kultusgemeinde, in the thirty years following the First World War catered for the religious and social needs of up to 190,000 Jewish souls.

The sudden transformation of a flourishing benevolent communal institution into a mass emigration and relief organisation was practically unexpected. In spite of the ever present menace of anti-semitism, the realisation of the impending fate of the Jewish community in Vienna came suddenly. The achievements of the highly professional abilities of the communally appointed included assistance in the acquisition of foreign visas, thereby saving about 12/13,000 Jews from certain death, and providing food and shelter for the thousands of families, suddenly deprived of their homes and livelihoods, turned into paupers overnight in 1938 and crowded together in near ghetto conditions in the 2nd District.

After the war, those traditions of unity and solidarity which had been established from it’s very beginnings, catering for all it’s varied constituents, were inherited by the new community which was rebuilt over the ashes of the destruction of the old, leading today to a flourishing and multifaceted kehilla.

More information on Jewish life and the main sites

https://www.ikg-wien.at/altosterreicher5-jpg-2/?lang=en

Der Wiener Stadttempel (Community synagogue) – 1st District, Inner City